Merge your commits

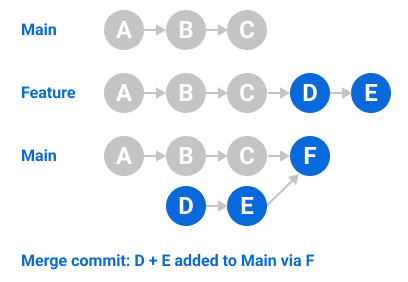

When you click the default Merge pull request option on a pull request on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance, all commits from the feature branch are added to the base branch in a merge commit. The pull request is merged using the --no-ff option.

To merge pull requests, you must have write permissions in the repository.

Squash and merge your commits

When you select the Squash and merge option on a pull request on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance, the pull request's commits are squashed into a single commit. Instead of seeing all of a contributor's individual commits from a topic branch, the commits are combined into one commit and merged into the default branch. Pull requests with squashed commits are merged using the fast-forward option.

To squash and merge pull requests, you must have write permissions in the repository, and the repository must allow squash merging.

You can use squash and merge to create a more streamlined Git history in your repository. Work-in-progress commits are helpful when working on a feature branch, but they aren’t necessarily important to retain in the Git history. If you squash these commits into one commit while merging to the default branch, you can retain the original changes with a clear Git history.

Merge message for a squash merge

When you squash and merge, GitHub generates a default commit message, which you can edit. The default message depends on the number of commits in the pull request, not including merge commits.

| Number of commits | Summary | Description |

|---|---|---|

| One commit | The title of the commit message for the single commit, followed by the pull request number | The body text of the commit message for the single commit |

| More than one commit | The pull request title, followed by the pull request number | A list of the commit messages for all of the squashed commits, in date order |

| Number of commits | Summary | Description |

|---|---|---|

| One commit | The title of the commit message for the single commit, followed by the pull request number | The body text of the commit message for the single commit |

| More than one commit | The pull request title, followed by the pull request number | A list of the commit messages for all of the squashed commits, in date order |

People with admin access to a repository can configure the repository to use the title of the pull request as the default merge message for all squashed commits. For more information, see "Configuring commit squashing for pull requests".

Squashing and merging a long-running branch

If you plan to continue work on the head branch of a pull request after the pull request is merged, we recommend you don't squash and merge the pull request.

When you create a pull request, GitHub identifies the most recent commit that is on both the head branch and the base branch: the common ancestor commit. When you squash and merge the pull request, GitHub creates a commit on the base branch that contains all of the changes you made on the head branch since the common ancestor commit.

Because this commit is only on the base branch and not the head branch, the common ancestor of the two branches remains unchanged. If you continue to work on the head branch, then create a new pull request between the two branches, the pull request will include all of the commits since the common ancestor, including commits that you squashed and merged in the previous pull request. If there are no conflicts, you can safely merge these commits. However, this workflow makes merge conflicts more likely. If you continue to squash and merge pull requests for a long-running head branch, you will have to resolve the same conflicts repeatedly.

Rebase and merge your commits

When you select the Rebase and merge option on a pull request on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance, all commits from the topic branch (or head branch) are added onto the base branch individually without a merge commit. In that way, the rebase and merge behavior resembles a fast-forward merge by maintaining a linear project history. However, rebasing achieves this by re-writing the commit history on the base branch with new commits.

The rebase and merge behavior on GitHub Enterprise Server deviates slightly from git rebase. Rebase and merge on GitHub will always update the committer information and create new commit SHAs, whereas git rebase outside of GitHub does not change the committer information when the rebase happens on top of an ancestor commit. For more information about git rebase, see git-rebase in the Git documentation.

To rebase and merge pull requests, you must have write permissions in the repository, and the repository must allow rebase merging.

For a visual representation of git rebase, see The "Git Branching - Rebasing" chapter from the Pro Git book.

You aren't able to automatically rebase and merge on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance when:

- The pull request has merge conflicts.

- Rebasing the commits from the base branch into the head branch runs into conflicts.

- Rebasing the commits is considered "unsafe," such as when a rebase is possible without merge conflicts but would produce a different result than a merge would.

If you still want to rebase the commits but can't rebase and merge automatically on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance you must:

- Rebase the topic branch (or head branch) onto the base branch locally on the command line

- Resolve any merge conflicts on the command line.

- Force-push the rebased commits to the pull request's topic branch (or remote head branch).

Anyone with write permissions in the repository, can then merge the changes using the rebase and merge button on your GitHub Enterprise Server instance.

Indirect merges

A pull request can be merged automatically if its head branch is directly or indirectly merged into the base branch externally. In other words, if the head branch's tip commit becomes reachable from the tip of the target branch. For example:

- Branch

mainis at commit C. - Branch

featurehas been branched off ofmainand is currently at commit D. This branch has a pull request targetingmain. - Branch

feature_2is branched off offeatureand is now at commit E. This branch also has a pull request targetingmain.

If pull request E --> main is merged first, pull request D --> main will be marked as merged automatically because all of the commits from feature are now reachable from main. Merging feature_2 into main and pushing main to the server from the command line will mark both pull requests as merged.

Indirect merges can only occur either when the commits in the pull request's head branch are pushed directly to the repository's default branch, or when the commits in the pull request's head branch are present in another pull request and are merged into the repository's default branch using the Create a merge commit option.

If a pull request containing commits present in another pull request's head branch is merged using the Squash and merge or Rebase and merge options, a new commit is created on the base branch and the other pull request will not be automatically merged.

Pull requests that are merged indirectly are marked as merged even if branch protection rules have not been satisfied.